The Rise, Retreat, and Reinvention of the Global Auto Show

For more than a century, auto shows have served as the grand stages upon which the global automotive industry introduced its most ambitious ideas. The earliest exhibitions in the early 20th century were celebrations of engineering progress and national pride. Paris, Detroit, Frankfurt, and later Geneva became annual rituals for consumers, journalists, and industry leaders. These shows were not simply marketing events. They were cultural markers that reflected the aspirations of their eras: the optimism of post‑war mobility, the glamour of the jet age, the technological bravado of the 1980s, and the global expansion of the 1990s and early 2000s. I went to my first auto show in 1985, in Philadelphia, eagerly looking at the gleaming new Porsches and Ferraris. As for photos, I still have one in a decidedly more affordable vehicle.

John Stech, the future Auto Ethnographer, at the 1985 Philadelphia Auto Show. Coincidentally, he would work with the Jeep brand 17 years later!

For decades, the formula remained remarkably stable. Automakers invested heavily in elaborate stands, dramatic unveilings, and carefully choreographed press conferences. A world premiere at Detroit or Geneva signaled a brand’s confidence. A sprawling pavilion in Frankfurt demonstrated industrial might. The shows were predictable in structure but powerful in influence. As a member of the Mercedes-Benz M-Class launch team in 1997, I distinctly remember the pride of representing the brand and vehicle on the show floor for an exhausting 11 days! Legions of Mercedes-Benz employees stopped by to have a look.

Russian introduction of the Jeep Cherokee with aid of a tiger! Moscow International Auto Show 2008. (Photo: John Stech, Managing Director, Chrysler Russia at this time.)

By the early 2010s, however, the ground began to shift. The digital revolution changed how consumers discovered products. The cost of participating in major shows rose sharply. Automakers questioned whether the traditional model still delivered value. The first public cracks appeared when Volvo announced in 2013 that participation in major auto shows was no longer a given. As Managing Director of Volvo Car Russia, I remember having to go see the owner of the Moscow International Auto Show at his Krokus Center office to inform that our brand would pull out of the 2013 edition of the show. My Marketing Director left that to me as he seemed to have some fear to deliver that news to the owner.

The Dodge Journey reveal in Russia. Moscow International Auto Show 2008. (Photo: John Stech, Managing Director, Chrysler Russia at this time.)

Soon after, the German premium brands began withdrawing from the North American International Auto Show in Detroit. Audi, BMW, and Mercedes‑Benz all stepped back from the event around 2018. Volkswagen, Ford, and Opel skipped the 2018 Paris Motor Show. Stellantis later reduced its presence at North American shows, citing cost pressures and shifting priorities. Even before the automakers pulled out of the shows, they began to heavily restrict who could attend. Whereas dozens, even hundreds, of people would attend from a brand in the past, eventually only a very few were provided with passes, particularly to the highly desirable press days.

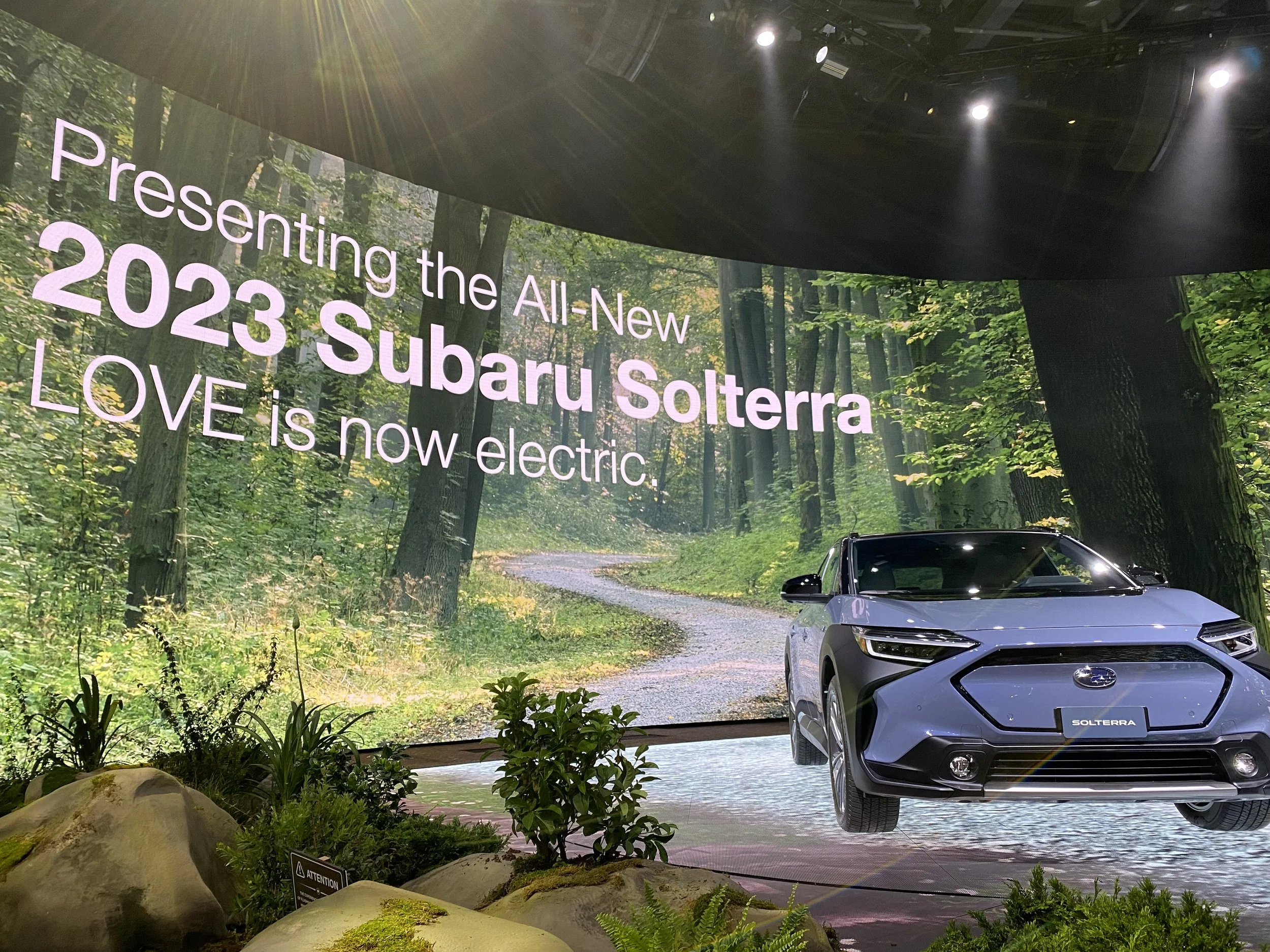

The Subaru Solterra EV reveal at the New York International Auto Show in 2022. (Photo: John Stech, attending the show as a “civilian”.)

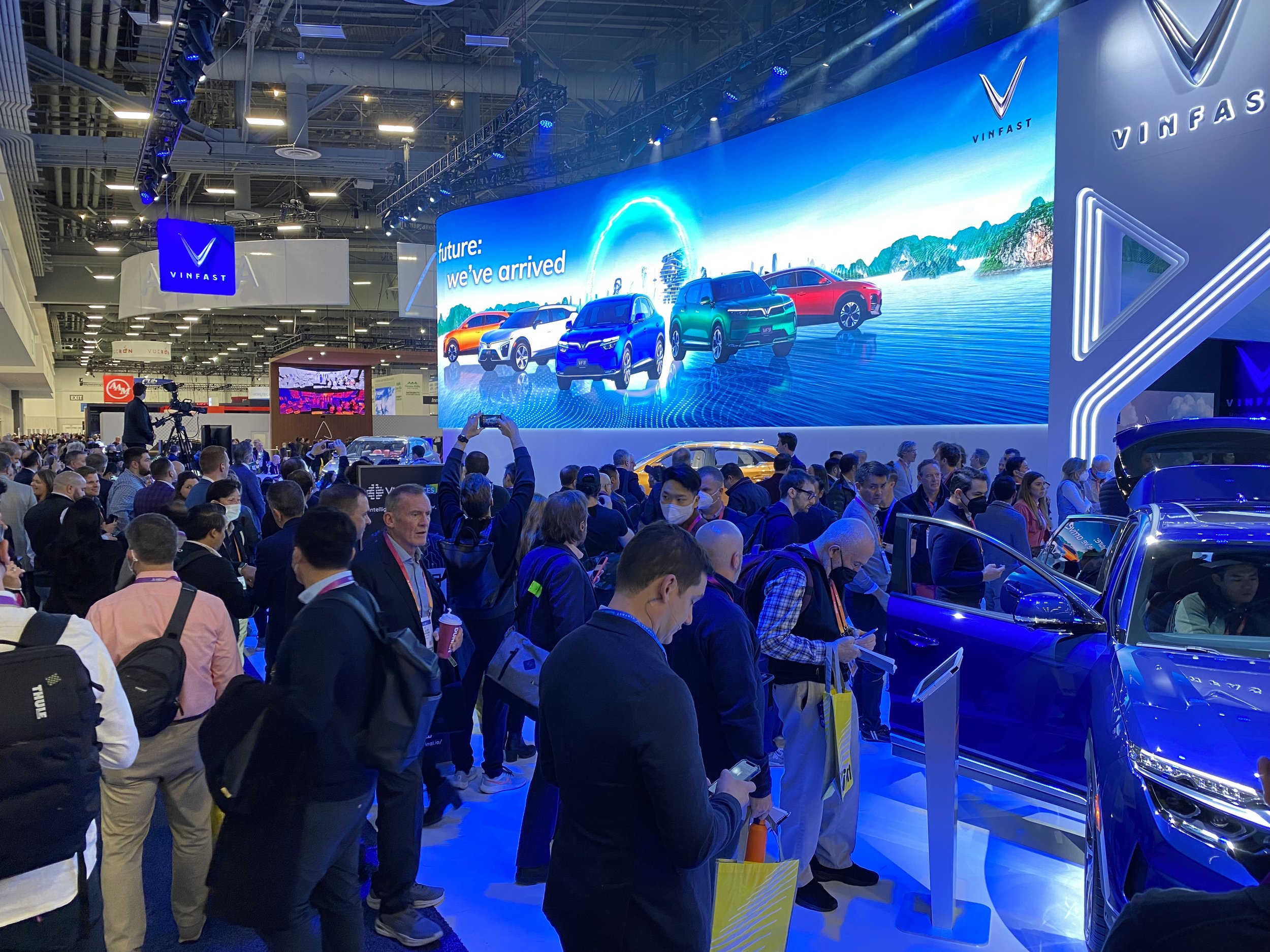

The reasons were consistent across brands. First, cost: a major auto show presence could run into the tens of millions of dollars, and the return on that investment was increasingly difficult to justify. “It’s just teenagers taking selfies in front of Porsches”, I once heard an executive say. Second, control: automakers wanted to dictate the timing, format, and narrative of their product launches. A livestreamed reveal or a brand‑owned event offered more flexibility and global reach. Or an invitation-only launch event could target exactly the right customers. Third, strategy: as companies shifted toward electrification and software, they prioritized engineering investment over traditional marketing. Fourth, competition: China’s auto shows grew in scale and importance, not to mention Las Vegas’ Consumer Electronics Show (CES), drawing global attention away from Europe and North America, and traditional auto shows.

These attitudinal changes had profound consequences for the world’s most iconic auto shows.

The North American International Auto Show in Detroit was the first to feel the full impact. Once the epicenter of global automotive news each January, the show began losing major exhibitors. Organizers attempted a reinvention by moving the event from January to June in 2020, aiming for a more experiential, indoor‑outdoor format. The pandemic forced cancellations in 2020 and 2021, breaking the show’s momentum. When it returned in 2022, participation was significantly reduced. By 2025, the event had reverted to January and had become a largely regional consumer show dominated by local dealer displays. The global press presence that once defined Detroit had evaporated. It was renamed to The Detroit Auto Show, scrapping the “International” moniker altogether.

Dodge Journey European debut at the Internationale Automobil Ausstellung in Frankfurt, Germany 2007. (Photo: John Stech, Managing Director, Chrysler Russia at this time. )

The IAA in Frankfurt faced a different but equally significant transformation. After decades as one of the world’s largest and most influential auto shows, the event struggled with declining exhibitor interest and growing public scrutiny. Environmental protests and shifting industry priorities accelerated the need for change. After the 2019 show, organizers made a bold decision: leave Frankfurt entirely. The event reemerged in Munich in 2021 as IAA Mobility, adopting a hybrid model that combined an indoor trade summit with an outdoor “Open Space” spread across the city center. This reinvention repositioned the show from a traditional automotive exhibition to a broader mobility platform. The new format emphasized bicycles, public transit, software, and sustainability alongside cars. The shift was dramatic, but it allowed the IAA to maintain relevance in a rapidly changing industry landscape.

The Volvo stand at the 2013 Geneva International Auto Show. (Photo: John Stech, Managing Director, Volvo Car Russia at this time)

The Geneva International Auto Show, once renowned for its neutrality and prestige, faced a more difficult path. After cancellations in 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023, the event attempted a return in 2024 with only a small number of exhibitors. The diminished scale made clear that the traditional Geneva model was no longer viable. In May 2024, organizers announced that the show would cease permanently in Switzerland after 119 years. The brand continues only through its newer Qatar edition, marking the end of one of Europe’s most storied automotive institutions. This was stunning since this was THE show for makers of luxury vehicles, supercars, and hypercars!

The Volvo stand at the Bogotá, Colombia auto show in 2018. (Photo: John Stech, VP Latin America and Canada Region, Volvo Cars at this time.)

These developments raise an important question: where does this leave consumers. Despite the industry’s strategic pivot away from traditional shows, public enthusiasm for seeing cars in person remains strong. Attendance at surviving shows, regional exhibitions, and experiential events suggests that consumers still value the tactile, communal experience of exploring vehicles. They want to sit in the seats, feel the materials, compare models side by side, and share the excitement with family and friends. The emotional connection that comes from physically engaging with a vehicle cannot be replicated through digital channels alone.

The massive VinFast display at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) 2023. (Photo: John Stech, Global Chief Marketing Officer, VinFast Automotive at this time.)

The future of auto shows will likely be shaped by this tension. Automakers are optimizing for efficiency, control, and strategic focus. Consumers are seeking experiences that are social, sensory, and immersive. The shows that succeed will be those that bridge these priorities: events that are less about spectacle and more about meaningful engagement, less about massive corporate displays and more about accessible, interactive exploration. The industry may no longer need the auto show as it once existed, but the public still values the opportunity to gather, discover, and dream. The next era of automotive exhibitions will depend on how well organizers and automakers respond to that enduring desire.

John Jörn Stech

The Auto Ethnographer